Translate Language

Box Jellyfish: Why It’s Earth’s Most Venomous Marine Creature

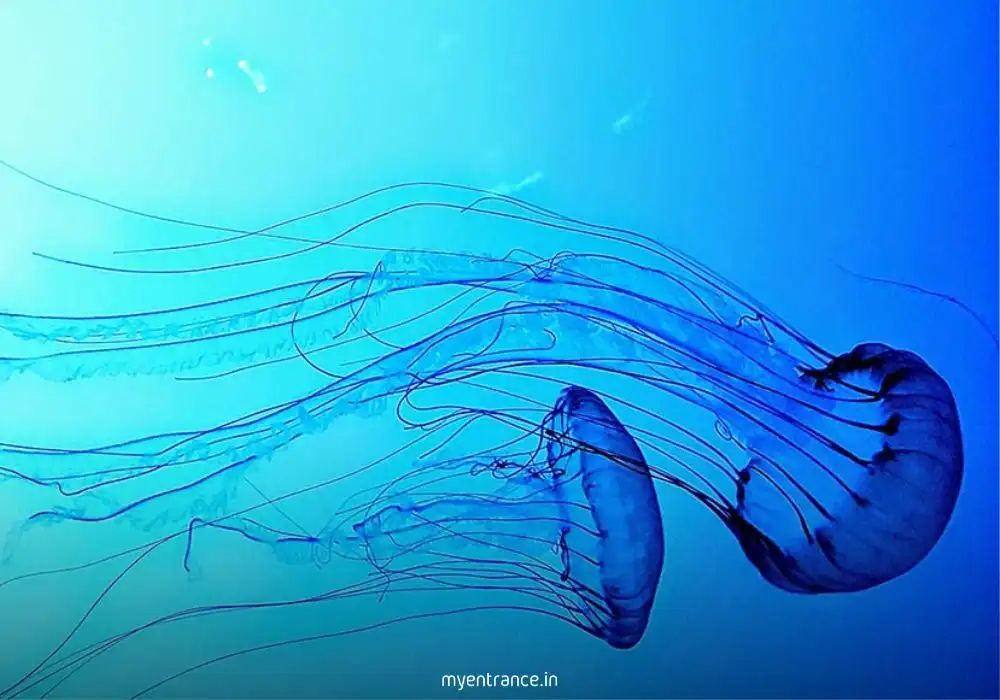

Picture yourself swimming in warm, tropical waters – a scene of paradise. But beneath the surface lurks an invisible menace: the box jellyfish. Delicate and nearly transparent, this creature’s beauty masks a lethal secret. For competitive exam students (UPSC, SSC, NIFT, etc.), understanding this marine marvel isn’t just about biology; it’s about grasping real-world science and survival tactics. Let’s unravel why this “sea wasp” is nature’s ultimate paradox of elegance and deadliness.

The Box Jellyfish: Anatomy and Behavior

Unique Physical Traits

Unlike common jellyfish, the box jellyfish (class Cubozoa) stands out:

Bell shape: A transparent, cube-like body up to 30 cm wide.

Tentacles: Up to 10 feet (3 meters) long, armed with millions of nematocysts – microscopic venom-injecting harpoons.

Movement: Agile swimmers (unlike drifting jellyfish), using a muscular velarium to propel themselves at 4 mph (1.5 m/s).

Habitat

Found in warm tropical oceans, often near coastlines. They hover below the water’s surface, making them hard to spot – a silent threat to swimmers.

Why Is Its Venom So Deadly?

Unmatched Toxicity

The Australian species Chironex fleckeri (nicknamed “sea wasp”) is the world’s most venomous marine animal. Its venom:

Destroys cells: Creates pores in cell membranes, causing potassium leakage.

Triggers cardiac arrest: Can stop a human heart in 2–5 minutes.

Rapid tissue necrosis: Causes severe scarring or limb damage even in survivors.

Fatal Statistics

A single jellyfish carries venom potent enough to kill 60+ adults.

69+ deaths recorded in Australia since the 1800s (Environmental Literacy Council).

50–100 global fatalities yearly from stings.

Speed of Attack

Medical experts describe the venom’s impact as “blinding speed”:

Cardiovascular collapse occurs almost instantly.

Delayed treatment often leads to permanent disability (e.g., chronic pain, mobility loss).

The Sting: Symptoms & Immediate Risks

Contact with tentacles triggers nematocysts to fire venom into the skin. Victims experience:

Physical agony: Burning pain, whip-like welts, and muscle cramps.

Systemic reactions: Nausea, headaches, hypertension, or cardiac arrest.

Long-term trauma: Psychological distress (PTSD) or recurring pain.

First Aid & Prevention: Life-Saving Protocols

Critical First Response

Vinegar (acetic acid): Douse the sting site within 30 seconds to neutralize unfired nematocysts.

DO NOT rub the wound: This triggers more venom release.

Emergency care: Rush to a hospital – antivenom must be administered within minutes to prevent death.

Proactive Safety Measures

Protective gear: Wear full-body lycra suits or wetsuits in “stinger season” (October–May in tropics).

Avoid high-risk zones: Heed warning signs in Australia, Thailand, or the Philippines.

Never touch washed-up tentacles: They remain toxic for weeks.

Scientific Breakthroughs: Hope on the Horizon?

Researchers at the University of Sydney used CRISPR gene-editing to develop a molecular antidote:

How it works: Blocks venom’s cell-destroying mechanism.

Limitations: Must be applied within 15 minutes; unclear if it prevents cardiac failure.

Future potential: Could revolutionize treatment in remote coastal areas.

Why This Matters for Competitive Exams

UPSC/SSC relevance: Questions on marine toxins, CRISPR, or first aid feature in GS papers.

Real-world context: Rising coastal tourism and climate change are expanding jellyfish habitats.

Key takeaway: Awareness saves lives – never swim unprotected in tropical waters during stinger season.

Final Thought: The box jellyfish embodies nature’s ruthless precision. For aspirants, it’s a case study in biology, ecology, and human resilience. Stay informed, stay safe!

Get 3 Months Free Access for SSC, PSC, NIFT & NID

Boost your exam prep!

Use offer code WELCOME28 to get 3 months free subscription. Start preparing today!